In his first week in office, President Donald Trump issued orders purporting to eliminate birthright citizenship, which is enshrined in the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, end diversity, equity and inclusion programs at federal agencies, and halt the work of the U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division. On Jan. 29, he issued an order regarding what schools can teach students about our nation’s civil rights history.[1]

In his second week in office, the president also fired two commissioners of the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, an agency empowered to enforce provisions of the nation’s civil rights laws.

That same week, before black box data had been analyzed, let alone a U.S. National Transportation Safety Board report issued, the president blamed an airplane crash in Washington, D.C., on the Federal Aviation Administration’s DEI efforts. In effect, he pinned the cause of an air disaster on minorities, women and the disabled.

These events must be juxtaposed against decades of painstaking and incremental efforts to achieve equality in our country by eliminating overt discrimination — and by addressing biases caused by government-sanctioned conduct that separated people based on their immutable characteristics. No doubt this is the history that our president does not want schools to teach.

While laws have been enacted and judicial opinions issued to prevent ongoing discrimination, the matter of bridging gaps in equality that are embedded in the law has been left to voluntary efforts ostensibly known as DEI.

The Lessons of Brown v. Board of Education

With the end of the Civil War, the nation adopted the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery, the 14th Amendment, designed in part to create equality, and the 15th Amendment, which proscribed the denial of voting rights based on race.

Despite the protections and proscriptions of those amendments, the states promulgated laws that separated the races and denied people rights based on their race. Judicial opinions that sustained such laws further embedded such bias.

In Plessy v. Ferguson, the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1896 opinion affirmed the doctrine of separate but equal, declaring that “if one race be inferior to the other socially, the Constitution of the United States cannot put them on the same plane.”[2]

Although Plessy involved a Louisiana law requiring separate railroad cars for the races, its logic was used to justify school segregation. Following Plessy, the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, or LDF, filed cases against public educational institutions for failing to provide separate but equal educational opportunities, facilities and teacher pay.

However, it was not until the 1950s — when five cases, each against a state or federal entity, made their way to the Supreme Court — that the LDF was positioned to wage a direct attack on Plessy by arguing that the rule of separate but equal, standing alone, violated the 14th Amendment.[3]

In 1954, Chief Justice Earl Warren penned his opinion in Brown v. Board of Educaton, which held that segregation in public education violated the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause.[4] The Brown opinion addressed four of the five cases in which a state entity was subject to the 14th Amendment.

The fifth case, Bolling v. Sharpe, challenged segregated public schools in the District of Columbia, which is subject to the Fifth Amendment, rather than the 14th Amendment.[5] Unlike the 14th Amendment, the Fifth Amendment does not include an equal protection clause.

The challenge Bolling posed was how to capture the logic of Brown — decided on equal protection grounds — and apply it within the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment.[6] Justice Warren’s words in his 1954 Bolling opinion were profound: The “concepts of equal protection and due process both [stem] from our American ideal of fairness.”[7]

Was the chief justice doing more than calling balls and strikes, as Chief Justice John Roberts once described the role of the judiciary?[8]

No. Justice Warren was stating the obvious. With a constitution that begins with the words “We the People,” and amendments that use the terms “due process” and “equal protection,” how could our rule of law not encompass an American ideal of fairness?

The Brown and Bolling opinions were issued at the height of the Cold War. They demonstrated to the world how our rule of law allowed individuals — albeit those who had been oppressed for ages — to invoke the legal system to successfully challenge the law itself.

Eradicating Embedded Inequality in all Sectors

Brown and Bolling were landmark decisions that only applied to the government. These cases did not eradicate private segregated lunch counters or hotels, or eradicate segregation in private education.

The Civil Rights Act was passed in 1964 to prohibit discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex or national origin. It was a significant step toward addressing private-sector discrimination. After its passage, the nation began the long arduous process of Civil Rights Act enforcement.

In 1971, Griggs v. Duke Power Co. came before the Supreme Court.[9] At its Dan River facility, Duke Power had implemented employment tests and a high school graduation requirement as prerequisites for most positions, which adversely affected black job applicants.

The trial court, and later the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, had held that these job requirements were facially neutral and thus not discriminatory.

The Supreme Court reversed, holding that facially neutral employment practices that have a disparate impact on protected classes can implicate liability under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.[10] Specifically, the court noted that such employment requirements had to be job-related.

The court in Griggs acknowledged two historic points. First, prior to 1964, Duke Power had discriminated in hiring at its Dan River facility.[11] Second, the North Carolina public education system had historically failed to afford black students an equal education.[12]

That discrimination was baked into the workplace, the education system and even the law was nothing new. Yet, what was becoming apparent was that even laws like the Civil Rights Act could not address a bigger problem: how to achieve equality without accounting for decades of past discrimination.

Suppose, for example, that the testing at issue in Griggs was job-related? Would a black applicant who had been subject to an inferior education system have been able to compete for a position? Under this scenario, Griggs would not necessarily have violated the law by denying employment, but the applicant would still have suffered from the blight of inequity.

None of this can be fully understood without really digging into how the government — the courts and the legislatures — have created inequality. Yet, on Jan. 29 Trump issued an executive order titled “Ending Radical Indoctrination in K-12-Schooling,” which may prevent students from reading or learning about the very laws and court decisions that explain the history of inequity — knowledge of which history is essential for navigating the path forward.[13]

To be clear, after the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the challenge was not just about enforcement and addressing schemes to evade enforcement. The challenge was also about addressing the long-term impact of decades of inequality, a matter that can only be understood through a study of unvarnished history.

Some of that history is buried in cases addressing mundane matters — for example, real estate transactions. In 1926, the Supreme Court in Corrigan v. Buckley, affirmed the right to enforce racially restrictive housing covenants that created and guaranteed segregated neighborhoods.[14]

Twenty-two years later, the Supreme Court’s 1948 decision in Shelly v. Kramer, found that using the courts to enforce such agreements violated of the 14th Amendment.[15] Yet the court in Shelly issued an opinion explaining how to discriminate without implicating the 14th Amendment:

We conclude, therefore, that the restrictive agreements, standing alone, cannot be regarded as violative of any rights guaranteed to petitioners by the Fourteenth Amendment. So long as the purposes of those agreements are effectuated by voluntary adherence to their terms, it would appear clear that there has been no action by the State, and the provisions of the Amendment have not been violated.

By the time Brown was argued, schools in this nation were segregated because of housing discrimination the created, in effect, whites-only and blacks-only neighborhoods, and hence blacks-only and whites-only local schools.[16]

In his oral argument before the court in Brown, Thurgood Marshall noted that the impact of any decision for the plaintiffs would be blunted by historic housing discrimination, which reduced the likelihood that a black child could walk to a neighborhood white school. The ultimate solution to the problem would come in later cases that addressed forced integration.

The Corrigan and Shelly opinions placed the imprimatur of government on the separation of the races. These cases are part of our history and need to be taught. They explain the existence of segregated neighborhoods, local schools that lack diversity, why red-lining is possible, and what makes it easy for government officials to channel education and other dollars along racial lines.

If there is bright spot in our history, it is the heroic dissenting opinions of jurists who spoke out when doing so was not popular. Consider, for example, the 1908 Supreme Court decision in Berea College v. Kentucky,[17] which upheld a Kentucky law precluding private colleges from teaching both black and white students on the same campus.

Justice John Marshall Harlan — dissenting as he did in Plessy — framed the issue as the government embedding discrimination:

If pupils of whatever race — certainly if they be citizens — choose, with the consent of their parents or voluntarily, to sit together in a private institution of learning while receiving instruction which is not in its nature harmful or dangerous to the public, no government, whether federal or state, can legally forbid their coming together, or being together temporarily, for such an innocent purpose.

I fear that the president’s Jan. 25 order will deter educators from teaching these cases — and the words of the justices who used their dissents and concurrences to set the record straight.

In 1968, in Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., the Supreme Court finally upheld an age-old reconstruction-era statute that addressed housing discrimination.

In his concurrence, former Justice William Douglas wrote:

The true curse of slavery is not what it did to the black man, but what it has done to the white man. For the existence of the institution produced the notion that the white man was of superior character, intelligence, and morality. The blacks were little more than livestock — to be fed and fattened for the economic benefits they could bestow through their labors, and to be subjected to authority, often with cruelty, to make clear who was master and who slave. Some badges of slavery remain today. While the institution has been outlawed, it has remained in the minds and hearts of many white men. Cases which have come to this Court depict a spectacle of slavery unwilling to die.[18]

Broader Implications of the Attack on Birthright Citizenship

While legislation and case law have institutionalized discrimination, the painstaking efforts of noted civil rights lawyers, like former Justice Thurgood Marshall and former NAACP first special counsel Charles Hamilton Houston, used the legal process to dismantle discriminatory law and precedent brick by brick.

Their tool in doing so has been the 14th Amendment. That this amendment may be vulnerable to an executive order regarding birthright citizenship is a chilling proposition.

The words at issue are clear: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside.”

Those words were written to address the Supreme Court’s 1857 decision in Dred Scott v. Sanford, which denied Scott the right to assert diversity of citizenship jurisdiction in a federal court because he was not — in the first instance — a citizen.

These words are so clear that when a challenge to the president’s executive order came before a U.S. District Judge John Coughenour in the U.S. District Court for the District of Washington, issued a temporary restraining order against its enforcement.[19]

At oral argument on Jan. 25, Coughenour, who was appointed by former Republican President Ronald Reagan, said to government counsel: “I have difficulty understanding how a member of the bar could state unequivocally that this is a constitutional order.”[20]

Addressing the Taint of Inequality

The president’s actions have no doubt caused discomfort, causing some to wonder, “Am I going to be OK?” There is reason to be concerned and to ask this question.

How this nation addresses biases that were baked into law, creating generations of inequality, is a complicated matter.

If life is analogous to a 100-yard dash, then DEI is about creating equality in the middle of the race, after some runners started the dash at a deficit.

This is a problem that our laws really do not address. And, unfortunately, courts cannot eradicate bias that has descended through generations and at times tempers the behavior of individuals in ways that are not obvious — even to the biased.

On the other hand, there is no doubt that DEI programs have become a hotbed for consultants and seemingly formulaic rules. There is also concern that some groups are not protected by DEI programs.[21] And there controversy — and indeed litigation — over whether such efforts are themselves discriminatory. These are legitimate matters for discussion.

It is apparent, however, that we have not reached the point where bias and discrimination no longer exist. It is hard to imagine that bias can be completely eradicated, and so the effort to create equality will always be an unfinished task.

One thing we cannot do is rewrite or sugar-coat our history. To chart a course forward, it must be fully understood. The question is whether we will be guided by the American ideal of fairness or driven to undo it.

_________________

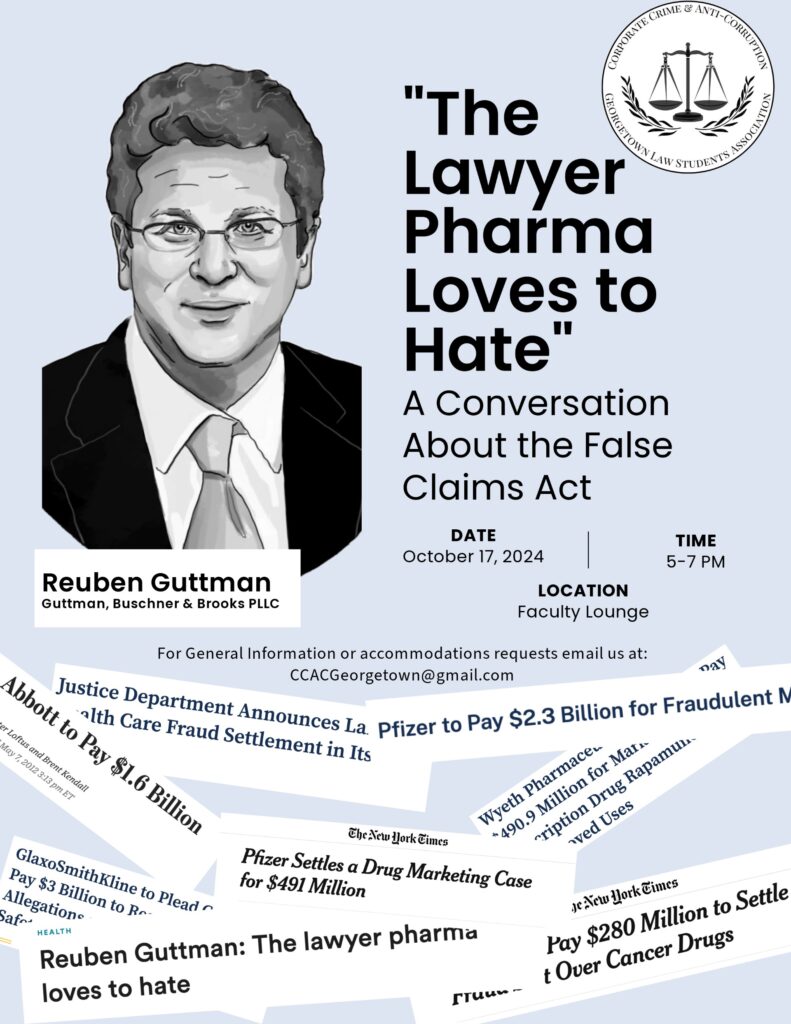

Reuben A. Guttman is a senior founding partner at Guttman Buschner PLLC.

[1] Ending Radical Indoctrination in K-12 Schooling — The White House.

[2] See, Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896).

[3] Those cases were Brown v. Board of Education, 347 US 483 (1954); Briggs v. Elliott, 163 U.S. 537 (1896); Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, 103 F. Supp. 337 (1952); Gebhart v. Belton, 91 A.2d 137 (1952); and Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954).

[4] See, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

[5] See, 347 U.S. 497 (1954).

[6] See, 347 US 497 (1954).

[7] The Court explained:

The Fifth Amendment, which is applicable in the District of Columbia, does not contain an equal protection clause as does the Fourteenth Amendment which applies only to the states. But the concepts of equal protection and due process, both stemming from our American ideal of fairness, are not mutually exclusive. The ‘equal protection of the laws’ is a more explicit safeguard of prohibited unfairness than ‘due process of law,’ and therefore we do not imply that the two are always interchangeable phrases. But, as this Court has recognized, discrimination may be so unjustifiable as to be violative of due process. [citations omitted].

[8] See, Chief Justice Roberts Statement – Nomination Process, https://www.uscourts.gov/about-federal-courts/educational-resources/supreme-court-landmarks/nomination-process/chief-justice-roberts-statement-nomination-process.

[9] See, 401 US 424 (1971).

[10] One could argue that the concept of disparate impact is as old — if not older — than Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. (1886).

[11] Justice Warren Burger noted: “The District Court found that, prior to July 2, 1965, the effective date of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Company openly discriminated on the basis of race in the hiring and assigning of employees at its Dan River plant.”

[12] Justice Burger explained: “Because they are Negroes, petitioners have long received inferior education in segregated schools, and this Court expressly recognized these differences in Gaston County v. United States, 395 U. S. 285(1969). There, because of the inferior education received by Negroes in North Carolina, this Court barred the institution of a literacy test for voter registration on the ground that the test would abridge the right to vote indirectly on account of race.”

[13] Ending Radical Indoctrination in K-12 Schooling — The White House.

[14] See, 271 U.S. 323 (1926).

[15] See, 334 U.S. 1 (1948).

[16] Trump is not unfamiliar with both housing discrimination and the work of the Civil Rights Division. In 1973, The Division filed United States of America v. Fred C. Trump, Donald Trump, and Trump Management Inc, in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York alleging violation of the Fair Housing Act of 1968. In 1975, the case was concluded with a consent agreement — signed by Donald Trump — that enjoined the Defendants from, among other things, refusing to rent a dwelling “on account of race, color, religion, sex or national origin.”[16]

[17] See, 211 U.S. 45 (1908).

[18] See, 392 U.S. 409 (1968).

[19] See, State of Washington et al. v. Trump et al., case number 2:25-cv-00127, in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington.

[20] Four courts have now blocked this Executive Order. https://www.delawareonline.com/story/news/2025/02/14/federal-judge-sides-with-delaware-blocks-president-donald-trump-birthright-citizenship-order/78542953007/.

[21] See, New York Times January 22, 2025, Does D.E.I Help or Hurt Jewish Students.